Wait - why can LLMs deal with spelling mistakes?

Overview

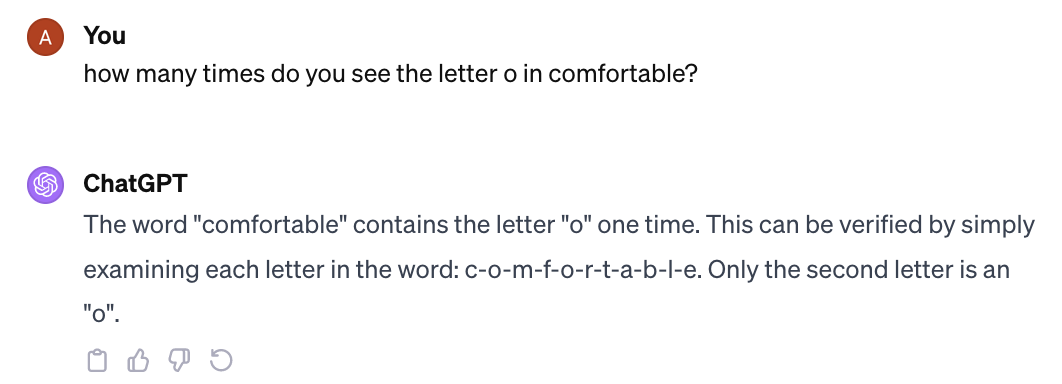

Why can’t LLMs reliably count the number of letters in a word, but they do know how to spell? E.g. why can LLMs not count the number of times “o” appears in comfortable:

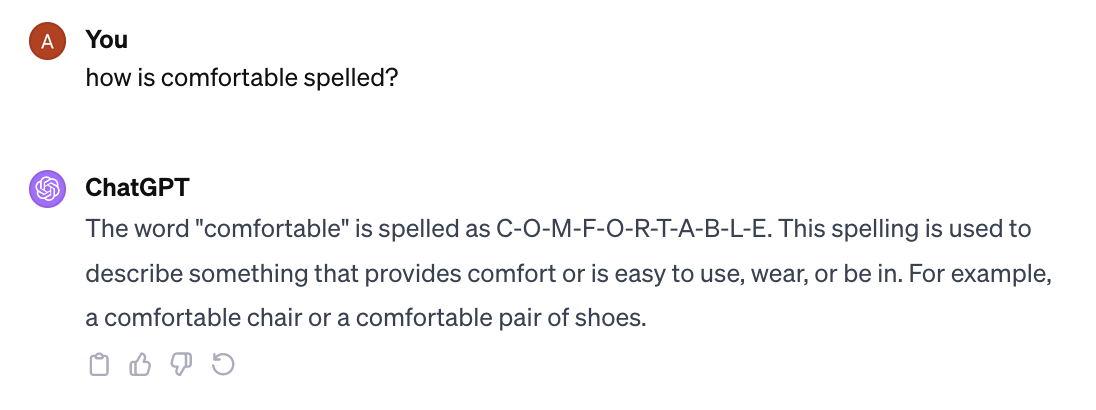

But they do know how to spell comfortable:

E.g.

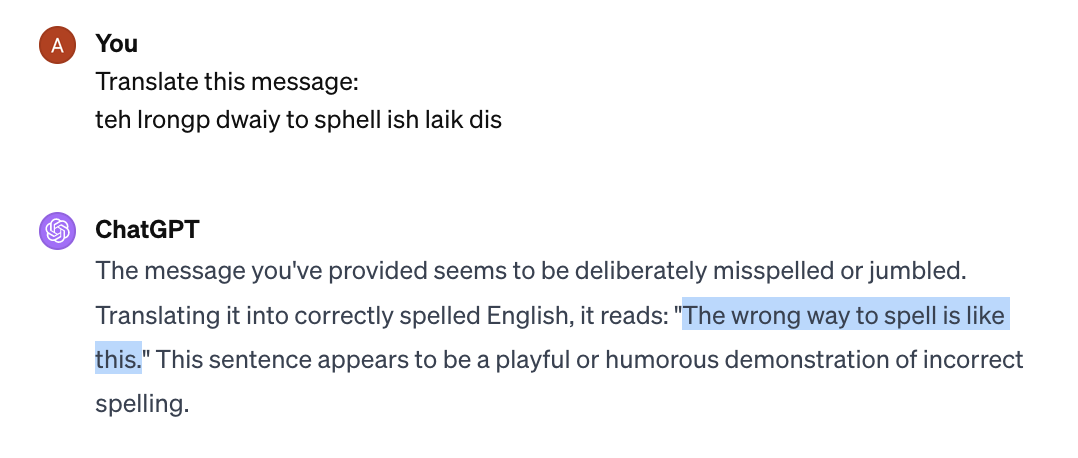

And how come they can deal almost ?

This question made me tinker with tokenizers for a bit. It helped me understand how tokenizers work, which I wrote up below to force an explanation, but it is still confusing why sub-token level comprehension works so well.

Tokenizers

When you want machine learning models to understand text, the first problem you need to solve is that you can’t really do math over letters or words or sentences. So we need to translate letters or words or sentences into some sort of object you can do math with - like a vector. The question of what level to abstract is pretty interesting - i.e. what is the “base unit” in this context? The word people use for that in language modeling is the “token” and naively you might think one of two positions; you make a token an individual word or you make a token an individual character. Both of these have some problems, and the solution people go for is somewhere in between.

Strategy 1: Just use words

Every word is a single “thing” that the model sees. Its the base unit. The problem with that is that you need to at some point define the entire vocabulary and this must be finite. How many words exist in the English language? Looks like the answer is in the 700,000-1,000,000 range (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_dictionaries_by_number_of_words). This is pretty large, which means there is a lot that the neural network has to learn. However, it gets much worse - you also have to consider things like other languages and spelling mistakes. So ~1M words in your vocabulary is probably wrong by some factor. If they are not in the vocab, the model would not understand it as a thing and it will have to be filed under “Misc. Words”. Bottom line - this is not a robust approach and doesn’t provide the flexibility that we need.

Strategy 2: use letters

The other thing that originally seems smart is to do it on a letter level. E.g. the AI would observe [a,b,c,d,e,f,g …. X,Y,Z (so lower case and capitals). You’ll probably quickly bump into the problem that special characters (. , ? ! @ $) show up in text, so we can add those (in fact lets just go with the whole ASCII set https://www.ascii-code.com/). With this you can form pretty much every word you need (at least in latin-script languages).

The problem with this approach is that your sequence gets super long. Long sequences are hard for many ML models, including transformers. The first sentence of this paragraph has 12 words, but 68 characters. Understanding a sequence of 12 things tends to be easier than understanding a sequence of 68 things.

The other thing is that the model needs to learn more things from scratch. E.g. the combination of the four characters “ the” is a pretty common thing that has a useful meaning, rather than having to learn “ “, “t”, “h”, “e”. Or the token “ing”, is a pretty useful unit in the English language as it tends to mean the same thing (i.e. make it an “ongoing action”, like from “walk” to “walking”). Ideally

Byte pair encoding

What most modern LLMs do is between these concepts – something called “byte-pair encoding”. The link above does a great job explaining it in detail, but the concept is to find combination of characters that show up a lot and use those as tokens. This can be entire words “ the” is a good example, but it can also be sub-words (e.g. “ing”).

Looking at some language models, it seems like the going vocabulary size is on the order of 30,000-50,000 GPT2 - ~50,000 https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1Zl3zSdli_epSfaoQ_HeBCuE6dkGWTowd#scrollTo=S5OKWOqHnmBg Llama 2 ~32,000 https://github.com/facebookresearch/llama/issues/29 MPT - ~50,000. https://huggingface.co/docs/transformers/model_doc/mpt

Bottom line: LLMs look at chunks of words

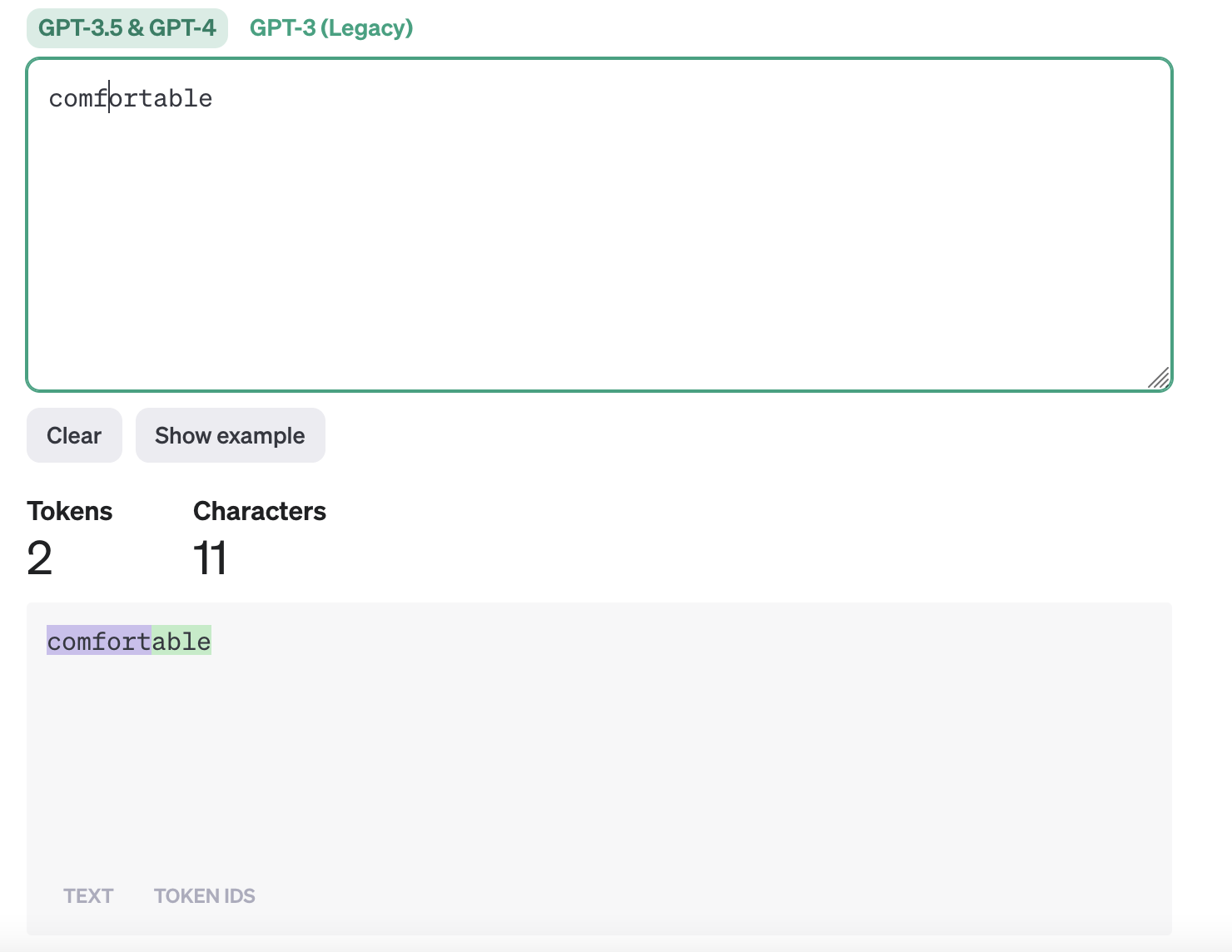

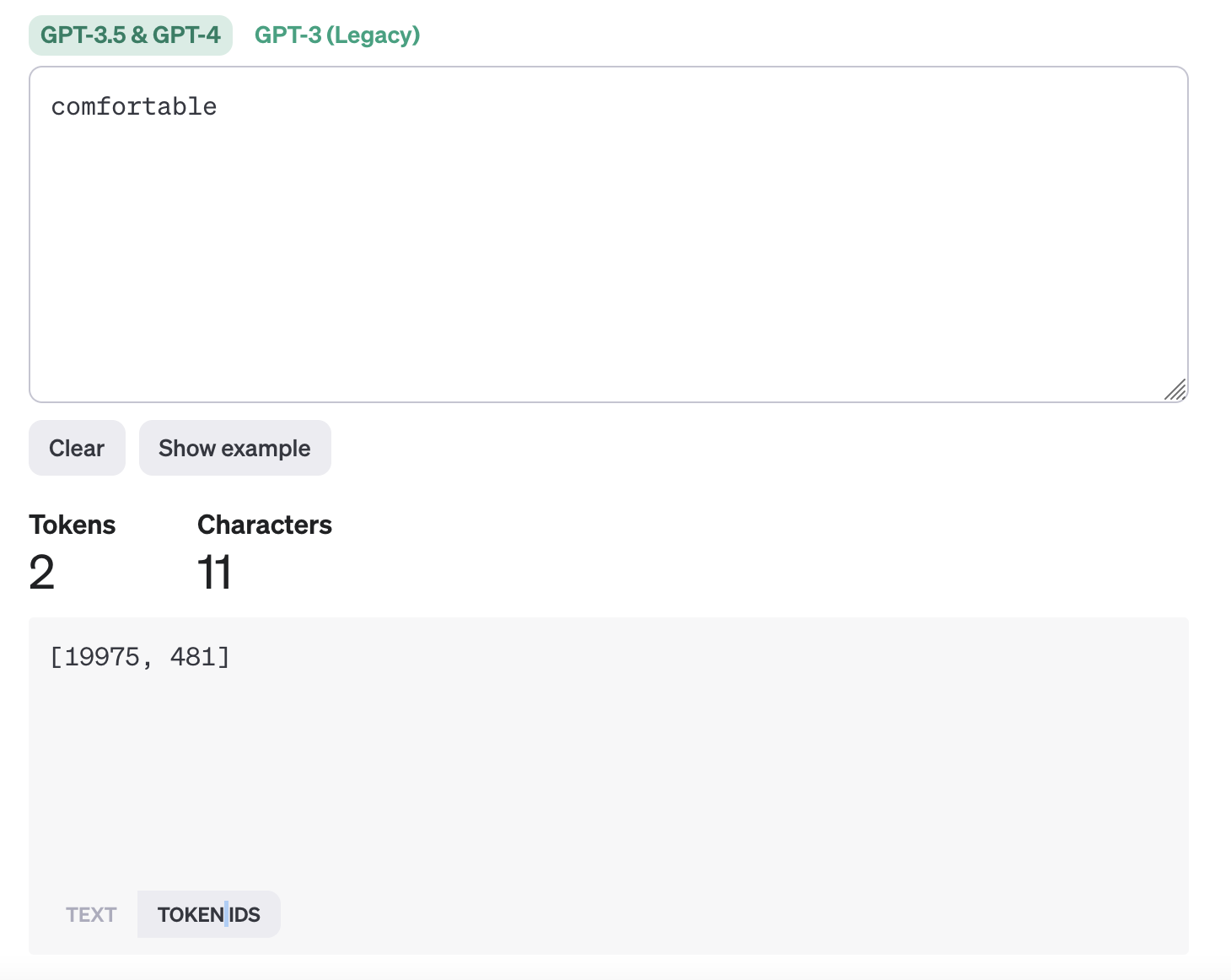

Ok, so LLMs don’t consider individual words, nor do they consider individual letters, but they consider something in between. To build some intuition for this, the OpenAI Tokenizer tool is worth playing with. For the more common words it seems like the whole word will fit into a “chunk”, but longer words like “comfortable” will be split into two tokens: “comfort” and “able”.

Specifically what happens is that the tokenizer gets the ID of these “tokens”. E.g. comfort is mapped to token ID 19975 and “able” is mapped to 481.

These token IDs are then mapped to vectors that are updated during training to best represent the kind of information that this token represent. That goes beyond the scope of this post, but the bottom line here is that: when you think of LLMs and spelling and counting letters in a word, or even counting words, what you need to consider is that they do not see letters or words. They see chunks of words. They have no idea what is contained inside of those chunks.

Or do they?

Why do LLMs know how to spell?

So if LLMs sees the world “comfortable” as [19975, 481], how does it know that it can be spelled as: C O M F O R T A B L E, which it outputs as: [34, 507, 386, 435, 507, 432, 350, 362, 426, 445, 469]

Or you can get it to output the spelling in a few different formats, like “c o m f o r t a b l e”, which, being lower case, are different tokens than the ones above: [66, 297, 296, 282, 297, 436, 259, 264, 293, 326, 384, 198]

Or tokens with leading spaces are different than with “-“ in-between. But you can get GPT4 to output its spelling like this as well: c-o-m-f-o-r-t-a-b-l-e [66, 16405, 1474, 2269, 16405, 3880, 2442, 7561, 1481, 2922, 5773]

So LLMs clearly have some level of understanding of what is contained in tokens, and there is some generalization here; it has learned to match the inside of tokens to many other tokens!

In fact, they are amazingly robust to spelling mistakes:

E.g.

But this is incredible. Imagine that you were in a room, and you were just given a series of numbers like [15339, 856, 836, 374, 57578, 323, 358, 1093, 18414]. After millions of such numbers are passed to you, you somehow start learning that 18414 can also be represented as [34, 473, 507, 356, 507, 445, 362, 350, 469]. The amount of reasoning and information processing that has to happen for this is amazing. And it just happens as a side-effect of trying to predict the next token!

That feels unbelievable. I would put a very low probability of this sort of thing happening automatically from next word prediction, and yet it does.